History and Timeline of the Tufa Field in Bath

The Tufa Field is located on the south side of the City of Bath. In earlier times, it was part of the Moorlands Estate, whose home is The Moorlands (also known as Englishcombe Court). This was home to the Ashford family, headed by Edwin Ashford, an eminent Doctor and amateur astronomer who added the prominent Tower in 1881. The Moorlands Farm land extended to the area now known as the Sandpits.

Parts were sold in 1928 for the housing now forming 89-123 Englishcombe Lane. The remaining Tufa Field is adjacent to Stirtingale Farm, and was used for dairy cattle grazing until just after the second world war.

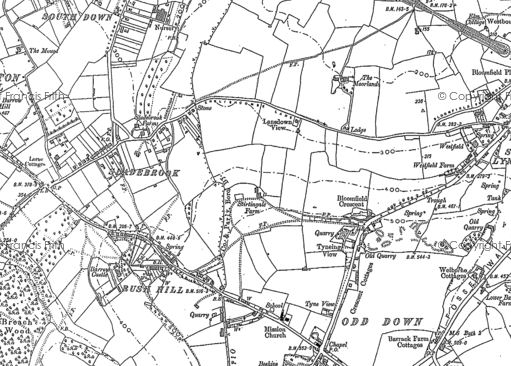

In this map the outline of the field can be seen in the centre next to the legend Lansdown View (today, 87 and 89 Englishcombe Lane).

Note the springs on the map of 1870 overlayed on a modern map. The main spring that now feeds the Sandpits stream, was the source of water for the Moorfields Farm.

By then, Stirtingale Farm (Stertingale on old maps as mentioned in this 1865 Bath Chronicle article) was an established farm, but the Moors Farm, belong to the Moorlands estate had gone .

The 1920’s was a time of rapid expansion in Bath, with the country lane running to the nearby village of Englishcombe starting to be developed along it’s length from east to west. Much of the land north and south of the lane was sold off by the Moorlands estate owners, the Ashford family. The farm became the site of the brickfields and latterly the Sandpits play area.

The streams from the hill were finally culverted following repeated floodings in areas of Oldfield Park .

The predominant architecture of the area is therefore 1920’s English – detached and semi-detached with ( by current standards) large gardens.

Aerial picture 1943 ( Historic England Copyright)

This 1943 USAF aerial picture shows the Tufa Field just visible in the bottom centre. Note The adjacent Stirtingale Farm fields are still in cultivation.

New-built houses in Englishcombe Lane, Bath, c 1930. Twerton roundhill in the background

Post-WWII, another phase of development took place, creating the rest of the locality in a 1950’s style. This was also the period of model architecture and the nearby Moorfields Estate was built, hailed as a model for a new society. Houses were designed to be light and spacious with good-sized gardens and spaces for play and recreation. Moorlands Schools, built at the same time, reflect this philosophy and still afford teaching spaces that are envied by modern schools.

Our field meanwhile sported a dairy house, and byre, the collapsed remains of which are still evident.

A feature of the adjacent SNCI is a bomb crater, (wrongly marked on official maps as a ‘pond’) , created during the Baedecker raids on Bath in WWII. Evidence of bomb debris damage to nearby houses is still visible. Unexploded ordnance in the field remains a remote possibility, since bombs landing in agricultural land were not routinely mapped.

The field then went into the fallow phase which led to today’s situation, with the eastern half being rented out for horse grazing for over 30 years. The council were fairly lax when it came to enforcing tenant responsibilities and the later tenants used the eastern end as a dumping ground for building and other waste. You can still see the ‘picnic table’ close to the site entrance.

Aerial view 1988 ( copyright Historic England)

By 1988 when this RAF photo was taken, the field was still a field with the byre showing up in dead centre. Also visible at the bottom of the shot is a bomb crater. (The wider shot shows another crater, for the first time indicating the path of the bomb stick from 1942).

From 1983 to 1986, multiple plans were approved to build sheltered bungalow housing on the site originally 32, then 31, finally 30, but an assessment deemed the land too difficult to build on, at the same time as local authority house building was stopped by central government.

This series of overhead views from Google Earth shows the state of the Field over 18 years.

The current phase of attempted development started in 2007, with pressure from government to meet quotas for house-building, and the field was entered into the Local Plan for up to 45 dwellings. Originally local planning officers recommended exclusion of the land from the plan on the grounds that greenfield sites should only be used as a last resort, accepting representations to that effect, but this was overruled by the government inspector, who ruled that there was insufficient evidence to support the BANES plan’s objective for house building numbers. Since then, these numbers have been easily exceeded, vindicating the original assessment by local officers that windfall and brownfield sites would meet the plan targets.

It is in the nature of successive plans, that decisions taken for earlier plans are not re-visited. Hence the field development designation was simply rolled over into the latest and current plan, without any reassessment of suitability or need.

Plans to build 37 houses on the site were approved in 2020, but then rescinded in favour of a new sheltered housing scheme and work commenced on this scheme in August 2023.

So today, while the Tufa Field has demonstrated the value of simply allowing nature to work, circumstances rather than need have determined its fate.

For an even older map of Bath of 1787 https://www.madisonoakley.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Bath-Map.pdf

Total views : 91309

Total views : 91309